This article was first published in Islamic Finance News on the 4th October 2017. For more information, please visit www.islamicfinancenews.com.

One of the biggest trends in recent years has been the exponential rise of ‘ethical’ investing — and its concurrent conflation, in the Islamic industry, with Shariah compliant finance. But while there may be many similarities, the two are not the same — and linking them can offer a misleading appearance to what are in reality two very different approaches to investing. Here at IFN, we think it is vital for the continued health and independence of the industry to draw a much-needed line in the sand.

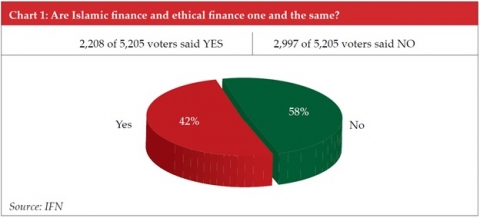

Over the past month, IFN conducted a simple poll asking readers: “Are Islamic finance and ethical finance one and the same?” Out of over 5,200 responses, a surprising 42% answered yes, while a slim majority of just 58% believe there are differences between the two.

We believe this is a worrying trend. There is no question that there is a strong overlap between Islamic and ethical investing. Draw a Venn diagram, and the intersection would be substantial. But the same could be said of the similarities between a cat and a dog, or a sheep and a cow. Does that make them the same animal? It does not.

What is ethical?

To start with, ‘ethical’ finance is a vast field with no one definition, whereas Islamic finance is clearly demarcated, regulated and defined with standard-setting bodies setting clear guidelines based on acknowledged Shariah principles.

“Ethical investing is a broad category and there are many different acronyms that are often used interchangeably but that actually mean very different things. We can talk about ethical investment, about SRI (socially responsible investing), about ESG (environmental, social and governance) — but basically, ethical investment is an approach that seeks to exclude certain types of business involvement that don’t align with an investor’s political, ethical, personal or religious beliefs,” explained Nadia Laine, the vice-president and EMEA head of ESG ratings at MSCI ESG Research. “It means different things to different clients. For one, it could be about excluding tobacco or alcohol companies, whereas for another it could be about avoiding corporate wrongdoing or human rights violations or animal testing. There is a wide range of criteria. Within that broad category we do see certain faith-based approaches, and Islamic is one of these.”

“There is no single definition of ethical investing,” agreed Meggin Thwing Eastman, the head of impact and screening research for MSCI ESG Research. “It is a broad concept that means different things to different people, and it is the individual investors and investment houses that define what it means to them. Islamic investing would fall into that category, and some of the issues overlap with the criteria in other subcategories, but it is an individual subset and the screening is specific to those requirements.”

Is ethical Islamic?

Can ethical investments be Islamic? Yes, on occasion, but that doesn’t make them automatically Shariah compliant. For example, the LionTrust UK Ethical Fund, which returned 30.2% in the 12 months to June 2017 (compared to 16.7% for its benchmark, the MSCI UK Index) has a number of investments fundamentally incompatible with Shariah: including a 30.4% weighting in conventional financial firms such as Legal & General, Prudential and Standard Chartered.

“As ethical investing includes not only religion but also political and environmental beliefs, Islamic finance and ethical finance could be totally different,” pointed out Dr Mohamed Damak, the global head of Islamic finance at S&P Global Ratings.

“A lot of people try and equate the two. There are undoubtedly some similarities, but there are equally as many differences, if not more,” agreed Hani Ibrahim, the managing director and head of debt capital markets at QInvest. “There is an overlap but they are not identical.”

“It is important to remember that not everything that is ethical is acceptable from a Shariah perspective,” warned Dr Mohamad Akram Laldin, the executive director of the International Shariah Research Institute. “For example, within the conventional fi nancial market, taking interest is not considered as immoral, and can therefore be acceptable in a so-called ‘ethical’ transaction. But from an Islamic point of view, it is not acceptable.”

“The Islamic package incorporates some very specific screens such as music, entertainment, conventional finance and dividend purification that you wouldn’t find in other ethical packages,” noted Laine. “Certainly not all ethical investments would meet Islamic screening criteria.”

“The main difference is in the financing tools used in ethical financing — these do not need to be Shariah compliant, which is the biggest issue,” said Yasser Dahlawi, CEO of the Shariyah Review Bureau, one of the leading global providers of Shariah certification. “The ethical financing movement includes some issues that match the higher ambitions of Islamic finance, such as sustainability. But Islamic finance is focused on a foundation in the real economy and a sharing of both the risk and the reward.”

“The logic is similar — you are trying to achieve something through a specific investment policy, be it ethical or Islamic,” commented Pierre Oberle, a senior business development manager at the Association of the Luxembourg Fund Industry. “In theory, they might look the same on the surface but underneath there are in fact many practical differences. Shariah funds go beyond ethical fund requirements — you have other requirements such as purifying dividends, prohibiting interest and having a Shariah board.”

“Islamic finance principles and the way of putting together transactions might be more restrictive than conventional ethical finance,” agreed Dr Mohamed Damak.

Is Islamic ethical?

So not all ethical investing is Islamic, but is all Islamic investing ethical? In this case, the scholars say yes.

“The general principle is that all Islamic investments are ethical, but not all ethical investments are Islamic,” said Dr Mohamad Akram.

“Broadly speaking and in theory, there should not be elements of Islamic finance that do not comply with ethical principles because the principles of Islamic finance are fundamentally ethical. They aim at protecting among others life, intellect and wealth,” agreed Dr Mohamed Damak. “If an investment is in line with Shariah principles, it should be fundamentally ethical.”

“Any Islamic investment is ethical in nature, and aims to meet the financial needs of participants with justice, equity and fairness,” added Rosie Kmeid, the vice-president of corporate communications at Path Solutions.

But is this really the case? What about when an Islamic investor participates in projects that can have a negative environmental impact, such as power stations, nuclear energy or oil and gas exploration?

For example, the Old Mutual Ethical Fund, which returned 11% over the past year (as of the 31st August 2017) does not invest in oil and gas exploration and distribution, mining, commercial banks, pharmaceuticals or medical technology. In contrast, the top five biggest holdings in the Aberdeen Global Islamic Global Equity Fund as of the 31st August 2017 were medical technology firm Sysmex, pharmaceutical companies Novartis, Johnson & Johnson and CVS Health Corp; and leading US oil and gas exploration firm EOG Resources. Clearly, in this case Islamic and ethical investing are certainly not one and the same.

“In reality, it depends on the definition of ethical principles,” admitted Dr Mohamed Damak.

Thwing Eastman agrees. “You can’t just come to us and say “I want to do ethical investing” without giving us more information on what you want, because there is no one definition. You might have investors that have particular ethical concerns that are not covered by the Islamic screens, and vice versa,” she noted.

“In practice, the application can vary between jurisdictions and even between institutions,” commented Dr Mohamad Akram. “The main issue is whether it will bring benefit or it will bring harm. And that can be very subjective. For example, investing in a coal-fi red power station might be considered detrimental to the environment, but it also creates jobs and provides power to heat homes. Legally speaking, there is nothing that prevents an Islamic investor from investing in a power station, it is compliant in that sense. But the Shariah board could rule against it if the negative impact is deemed to [be] severe. It is like a person consuming sugar. There is no rule against eating sweets. But if a person consumes to the detriment of his health, should his Imam intervene?”

A new horizon

So what happens if you apply both Islamic and ethical criteria to an investment? This is certainly an option, and firms like Saudi Arabia’s Sedco Capital and India’s Tata Ethical fund are doing exactly that. In August this year, Sedco launched what it called a “groundbreaking new investment strategy combining traditional Shariah finance principles with ethical investment”.

“We invest in companies that have strong governance, clear structures and a prudent level of leverage,” explained CEO Hasan Al Jabri. “In short, while we target strong returns and performance, we ensure that our investments benefit society, comply with Shariah and ESG investment principles, while avoiding excessive leverage and non-transparent investment structures.”

However, this adds further limitations while imposing additional burdens from a compliance perspective. “Funds that promote themselves as both ethical and Islamic are really narrowing the universe of what they can do,” said Hani. “As an Islamic fund manager, you have already filtered out a lot of investments and there are a lot of investments you do not have access to. The same holds true of ethical investing. When you combine the two, your options become very limited and your universe becomes very small.”

You also need two lots of certification, pointed out Yasser, thus increasing the compliance costs. “If a product is certified as ethical but using an interest-based financing model, it would not be Shariah compliant even though Islam might support the ethical goals of the product. This is the biggest issue,” he warned. “You need separate certification to make the differences clear to the stakeholders. You could possibly develop combined criteria to demonstrate that the investment meets both sets of requirements. But no such certification currently exists. At the moment, having robust standards in place is a priority to make sure investors know the difference between the two approaches.”

Positive convergence

That is not to say that there are no similarities or that the crossover between Islamic and ethical financing is not a valuable tool for expanding access and understanding. In fact, this could be one of the biggest benefits of the convergence between the two — a new audience for Islamic investments interested in its ethical foundations. “The main attraction is to appeal to a broader range of investors,” agreed Oberle. “It is mostly a branding exercise.”

However, a new trend of positive investing could bring the two sides closer together.

“Both conventional ethical investors and Islamic investors want their investments to meet certain criteria that go beyond just a financial return. There is a fundamental overlap between the two kinds of investing in that they are applying a filter to tailor it to their individual beliefs,” commented Michael Bennett , the head of derivatives and structured finance in the Treasury Department of the World Bank. “Traditionally, the way these beliefs have been expressed in investing is through exclusion through negative screening. The place where there has been some divergence recently is that more and more ethical investors are applying a positive filter — they want to see where the proceeds are going and they want the proceeds to support specific types of activity. That is where Islamic investors have not been so proactive — for the most part, they are still using negative filtering and are less concerned with the use of proceeds.”

However, this is gradually changing. “We are seeing some Islamic investors broadening out to incorporate more ESG themes like climate change or corporate governance or social impact, and identifying companies that are making positive contributions,” said Laine. “This is a fairly new trend within ESG and I suspect that some Islamic investors will be interested in the other side of the coin. But that would require additional tools above and beyond the standard Islamic package.”

Social Sukuk

Nowhere is this positive trend more prominent than in the case of green Sukuk, an area that has received much media attention despite relatively little actual activity.

“The rise of green Sukuk shows that Islamic investors are also now looking at the use of proceeds,” said Bennett. However, few deals have so far emerged to drive this forward. In 2014, the World Bank Treasury was instrumental in tying the Islamic and ethical markets together through its support of a US$500 million Sukuk facility from the International Finance Facility for Immunization (IFFIm), bringing the concept of socially responsible investing to the Sukuk market. “The IFFIm Sukuk seemed to be the first time that the use of proceeds was explicitly ethical: to support vaccine programs,” said Bennett . “We marketed the issuance around a double angle: Islamic both in terms of structure, and also in terms of principle.”

Malaysia’s sovereign wealth fund Khazanah Nasional followed up with a groundbreaking RM100 million (US$23.62 million) SRI Sukuk facility in 2015 to fund a schools program in partnership with the Ministry of Education, and in June this year returned to market with its second RM100 million tranche.

Yet these issuances have been the exception rather than the rule. This highlights a key difference between the two. For Islamic bonds, the emphasis is on their grounding in the real economy and their Shariah compliant structure, while for green bonds it is their use of proceeds that gives them their ethical credentials.

“The essence of Islamic finance is real world economic transactions that add real value,” said Hani. “There might be an overlap between green bonds and Sukuk, but green bonds are not always based on assets, and they do not have the same underlying aim to support transactions in the real economy. Green bonds are doing great work but the majority are classified as green because of their use of proceeds as opposed to financing an identified green project. Sukuk, particularly those structured around Ijarah or Mudarabah, play a different role in supporting real economic activity. Does that count as ethical finance? It depends on the definition of ethical.”

A slow process

It is here that the crux of the argument lies. Without a standard definition, it will remain impossible to equate ethical investing accurately with Islamic finance. But could the current trend for conflating the two in fact be responsible for holding back the industry?

“If you already believe that Islamic finance is ethical and ethical finance is Islamic, then there is no incentive to change or to improve,” warned Bennett. “To what extent will this slow down the process of evolution?”

IFN believes that a line needs to be drawn between the two. Not to the detriment of the industry, but on the contrary, to celebrate its unique and diverse identity.

For full article Click Here